State Fairs: Growing American Craft: Four Questions for Exhibition Contributing Curator Jon Kay

Jon Kay with Jason Baird Jackson

Indiana University Bloomington

Jon Kay is Director of Traditional Arts Indiana and an Associate Professor of Folklore at Indiana University Bloomington. In this exchange I pose questions to him about the new Smithsonian exhibition and catalogue State Fairs: Growing American Craft. Find details about the exhibition at the end of the interview.

Jason Baird Jackson (JBJ): Jon, you have just returned from a trip to Washington, DC for the opening of the exhibition State Fairs: Growing American Craft, which will run through September 7, 2026 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Renwick Gallery. The Renwick is the part of the Smithsonian devoted to craft. Before I ask you about your role in the exhibition and the associated catalogue (Mary Savig, ed., State Fairs: Growing American Craft. Smithsonian Books, 2025), can you tell me about the opening? What did you see? What did you do? Who went with you? What was most memorable?

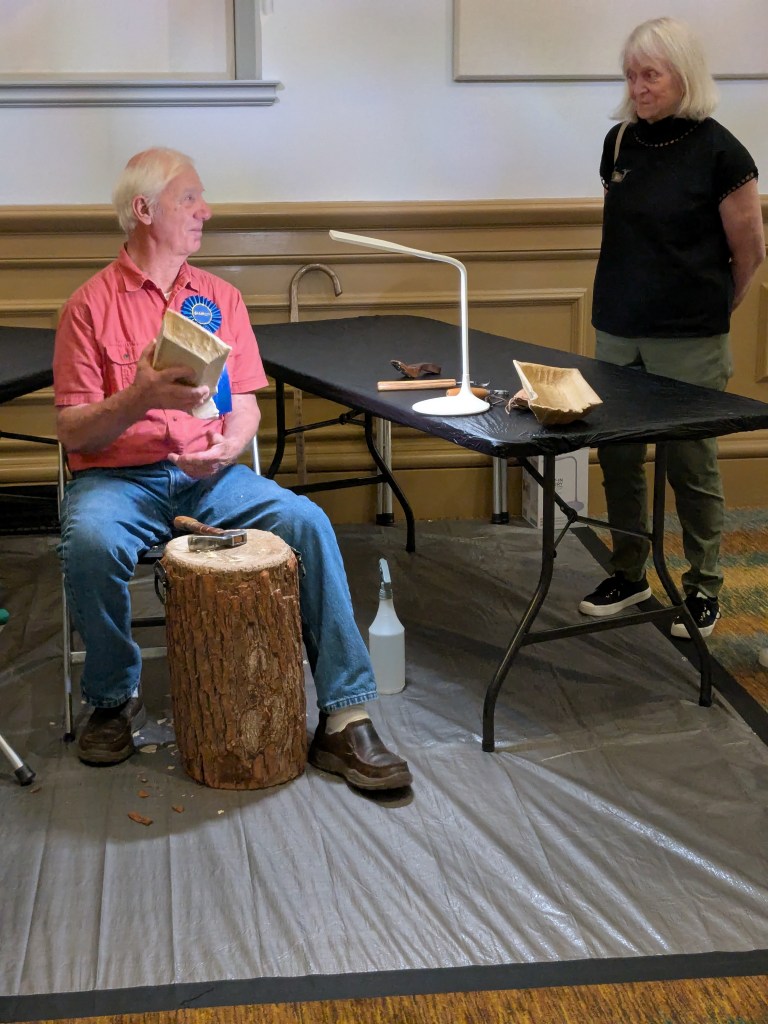

Jon Kay (JK): Thank you for the opportunity to reflect on my recent trip to Washington, DC, where I attended the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM)’s after-hours celebration of the exhibition State Fairs: Growing American Craft at the Renwick Gallery. I participated in the event with Keith Ruble, a bowl hewer and longtime demonstrator in the Indiana State Fair’s Pioneer Village (Figure 1). Keith was named a State Fair Master in 2001—well before I became director of Traditional Arts Indiana (TAI)—a testament to the longstanding recognition of his work.

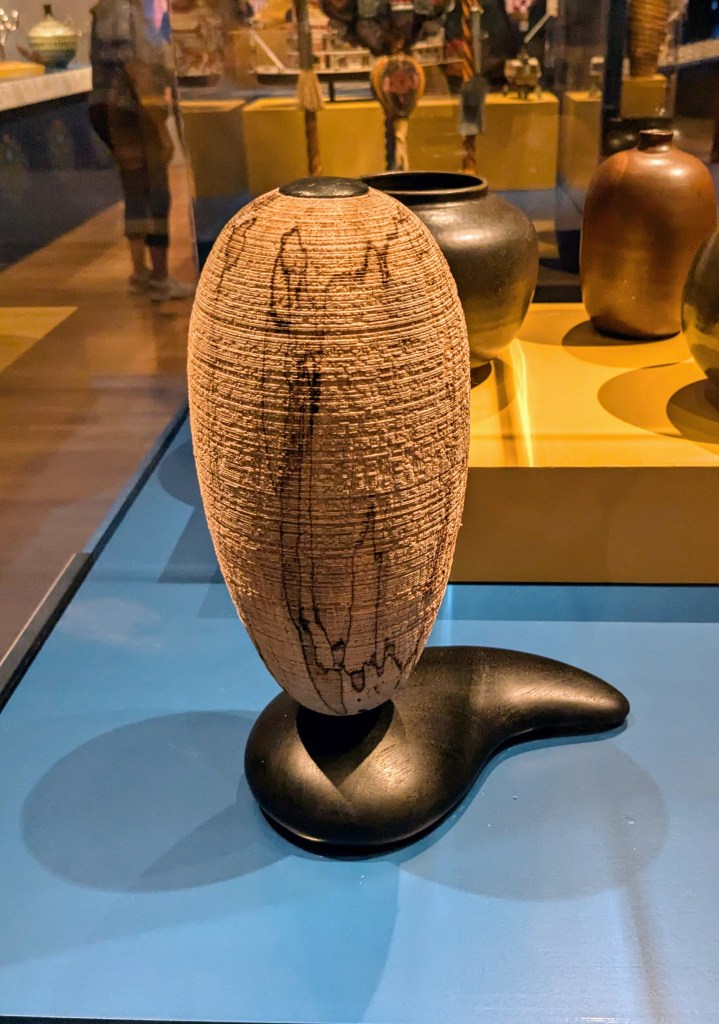

From 2001 to 2021, TAI partnered with the Indiana State Fair to honor its veteran participants through the State Fair Masters program. Each honoree was selected for their skill, excellence, and deep knowledge in their discipline, as well as for their commitment to passing on that knowledge within their communities. The program emerged in the years following the untimely death of Bill Day, an early Pioneer Village demonstrator and Keith Ruble’s bowl-hewing mentor. It was fitting, then, that both Keith’s and Bill’s bowls were featured in the Renwick’s exhibition (Figure 2).

Keith had been invited to demonstrate at the exhibition, but initially declined—he and his wife, Susie, don’t fly, and he didn’t feel up to driving to DC. When he told me this, I offered to take him. He agreed. So, the day before the celebration, Keith, Susie, my wife Mandy, and I made the twelve-hour trip to the Renwick.

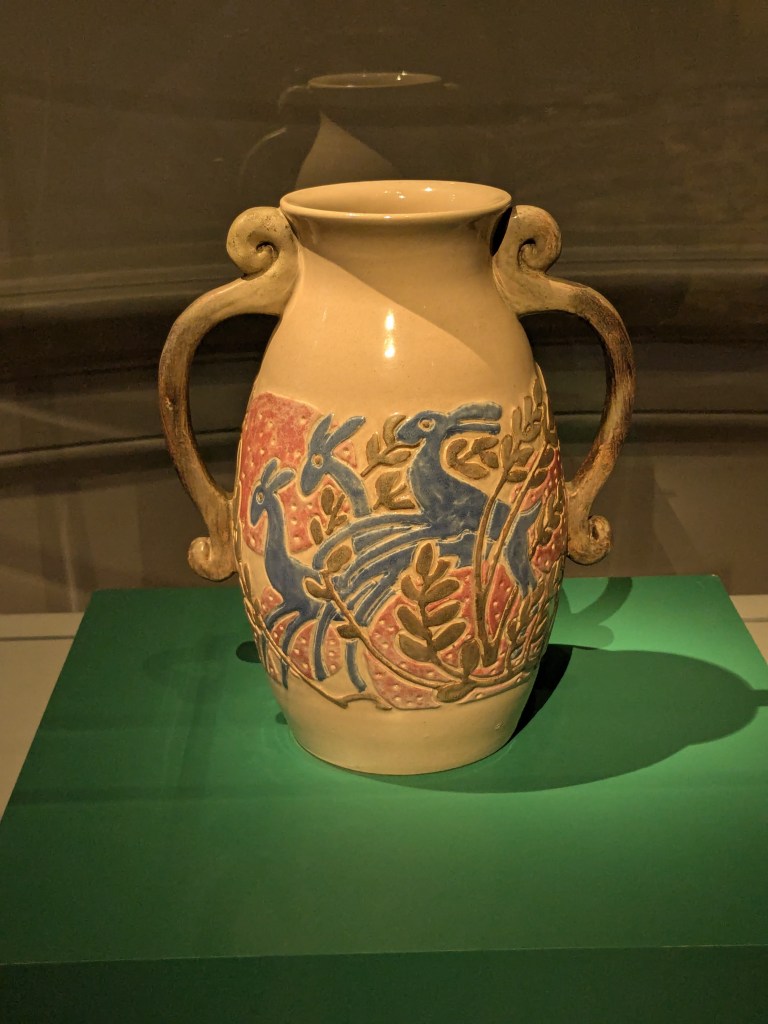

On our first morning in DC, we walked to the Renwick Gallery to view the exhibition and deliver several hand-hewn bowls that Keith had made for the museum’s gift shop (Figures 3 and 4). I imagine your future questions will explore the exhibition’s content in more detail, but for now, I’ll say it was a remarkable showcase of crafts by artists who have exhibited, competed, and demonstrated at state fairs—past and present. From pottery and crop art to canned goods and quilts, the exhibition underscored the central role of craft in state fairs since their inception in 1841 (Figures 5, 6, 7, and 8).

The celebration brought together many of the featured artists and their families, including saddle maker Bob Klenda from Kimball, Nebraska; canner Rod Zeitler from Coralville, Iowa; and basket maker Polly Adams Sutton from Seattle, Washington (Figures 9, 10, 11). While the artists enjoyed seeing their work on display, the event also created a meaningful space for state fair craftspeople from across the country to connect and share stories. The atmosphere was one of mutual appreciation. In a culinary nod to fair traditions, the Renwick served corndogs, cornbread, corn pudding, and other fair staples. It was a festive and memorable evening.

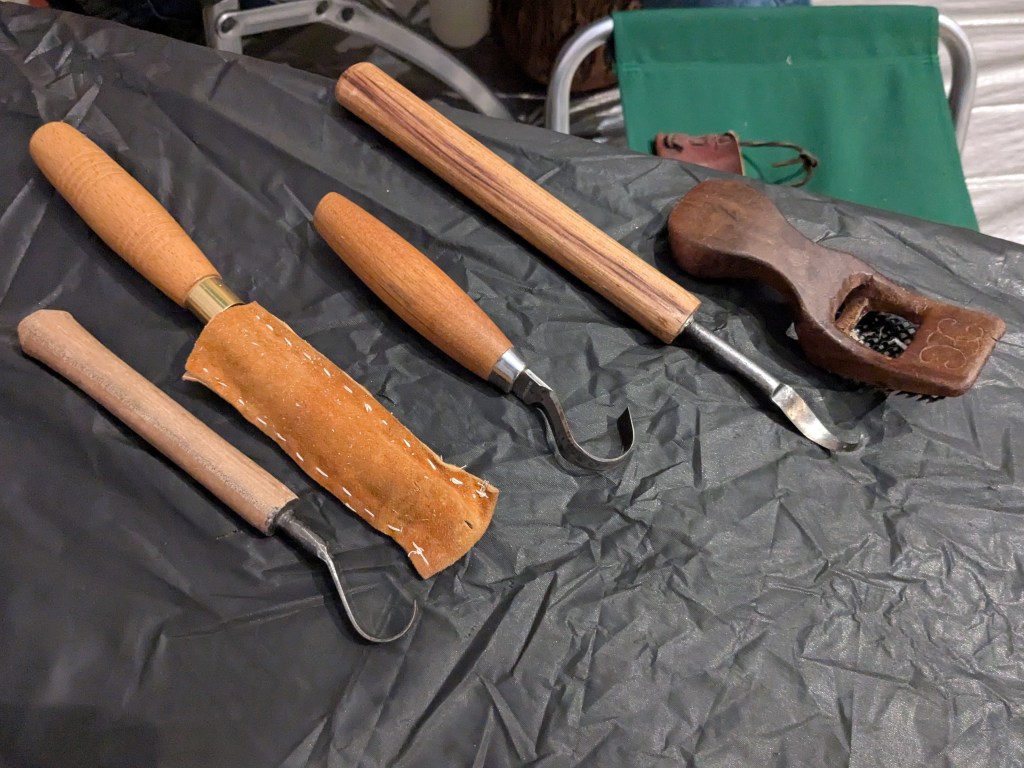

The following day, Keith demonstrated his craft at the Renwick. Concerned about wood chips, the events team taped down tarps and provided tables and chairs. Keith’s setup was minimal—just a few tools: a bowl adze fashioned from a ball-peen hammer, a bent gouge, a couple of spoon knives, and a hand-rasp scraper (Figure 12). But what really caught people’s attention was his sassafras stump with luggage handles, which he uses as a chopping block (Figure 13).

Throughout the day, Keith worked on an Indiana-shaped bowl, answered questions, and shared stories. He spoke about his mentor, Bill Day; his wife’s tolerance for him chopping in the living room; and his “mother-in-law” bowls—his name for the ones that crack (Figure 14).

Alongside Keith were two other demonstrators: Martha Varoz Ewing from Santa Fe, New Mexico, who practices traditional straw appliqué, and Samuel Barsky from Baltimore, Maryland, known for knitting custom sweaters of his own design (Figure 15 and 16).

Soon after Keith began, the rhythmic chop, chop, chop of his adze echoed through the gallery, drawing visitors to the demonstration area. From 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., the artists worked and engaged with the public. Keith noted that he didn’t even finish the bowl he brought to work on. I assured him that the Smithsonian didn’t mind. There was a steady stream of visitors throughout the day, and the exhibition, as a whole, was very well attended.

JBJ: I am glad that you and Mandy, Keith and Susie had a great time at the exhibition and its opening events! With the scene set now, can you tell me about your role as one of the “contributing curators” working with lead curator Mary Savig?

JK: From 2004 to 2022, I coordinated the Indiana State Fair Masters Program as part of my work directing Traditional Arts Indiana. For this program, I conducted oral history interviews, created exhibition panels, and produced documentary films.* My friend Betty Belanus, a retired curator at the Smithsonian Institution’s Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and Indiana’s first state folklorist in the 1980s, was aware of my long-standing work with the Indiana State Fair. When Mary Savig, Chief Curator of the Renwick Gallery, began planning the exhibition State Fairs: Growing American Craft, Betty suggested that she reach out to me to help identify potential Indiana craftspeople to feature.

Mary and I met at the 2023 Indiana State Fair, where I gave her a tour of the fairgrounds. The State Fair Masters program, as I mentioned earlier, celebrated the work of longtime fair participants—from apple growers and hog breeders to pie bakers and weavers—highlighting the artistry embedded in fair traditions. While many of these practices have aesthetic dimensions, the Renwick is a craft gallery, so performance-based traditions, such as baton twirling, clogging, and washboard playing, were outside the scope. I joked that while I could make a case for seedstock swine breeding or miniature donkey husbandry as art forms, jars of jelly and pickles were probably as close as the exhibition would get to these more ephemeral crafts.

As we walked the fairgrounds, Mary and I discussed her vision for the exhibition and my nearly two decades of work with the Indiana State Fair. The State Fair Masters program had ended in 2023, so I was especially reflective during our visit.

Our first stop was the Indiana Arts Building, formerly known as the Home and Family Arts Building. In the basement, baked goods and canned items were exhibited; the main floor featured quilts, needlepoint, weaving, crochet, and knitting. The building also featured paintings, photographs, and other artworks that had been entered in various fair competitions. I introduced Mary to longtime building coordinator Nancy Leonard, and then we talked with Mary Schwartz, a 2013 State Fair Master who was recognized for her needlepoint artistry.

Next, we visited the Pioneer Village, located across the fairgrounds and surrounded by antique tractors and historic farm implements. The Village showcases farming practices, music, and crafts from Indiana’s Depression Era and earlier. I introduced Mary to the wheelwrights and blacksmiths, and Charlie Carson who trains oxen and makes yokes. In the Pioneer Village Building, Mary talked with quilters, weavers, and broom makers—but what truly captured her interest was the bowl hewing.

I had recently curated an exhibition at the Swope Art Museum in Terre Haute, Indiana that featured several bowl makers who demonstrated at the fair. I introduced Mary to Keith Ruble and Blaine Berry, both of whom would later be featured in the Renwick exhibition. I also secured a large sassafras bowl made by Bill Day for the exhibition. I loaned the gallery a tulip poplar bowl shaped like Indiana, which Keith had made for me for the 2016 Bicentennial of Indiana Statehood. In addition to recommending artists, I shared ideas for potential craft inclusions. Mary ultimately acquired a settee and two Windsor chairs from Blaine, which the Smithsonian purchased (Figure 17).

By the end of our visit, Mary had identified about ten potential Indiana artists for the exhibition. A few months later, she told me that she needed to pare down the list, because the exhibit included more craftspeople from Indiana than any other state. The final roster included bowl maker Keith Ruble, chairmaker Blaine Berry, basket weaver Viki Graber, woodturner Betty J. Scarpino, and potter Kelly Bohnenkamp, who loaned her whimsical “corndog vase” (Figures 18-20). The exhibition also included works by two historical Indiana craftspeople: a vase by Mary Overbeck (1878–1955) and the large bowl made by Bill Day (1915-1999) (Figure 21).

JBJ: I am glad that you could help the craftspeople of Indiana gain recognition from this major exhibition at a key world museum devoted to craft. I mentioned the catalogue for the exhibition at the start. Can you tell readers what they will find in that catalogue and what your contribution to it is?

JK: The exhibition catalog, State Fairs: Growing American Crafts, is a companion book published by Smithsonian Press (Savig 2025). It connects the narrative threads of the exhibition, as outlined by editor Mary Savig in the introduction. The chapters then highlight key themes, including “4-H and Youth Participation,” “Creative Arts Competitions and Women’s Collectivity,” “Indigenous Fashion Shows,” and “Studio Craft Competitions.” My chapter ended up being more focused than the others, centering on the Pioneer Village at the Indiana State Fair.

Mary and I initially discussed framing the essay around creative aging in heritage events, but ultimately, she felt a tighter focus on the Pioneer Village would serve the book better. For my chapter, I drew on decades of interviews with participants in the Pioneer Village. In fact, I had to work hard to stay within the word count. I hadn’t realized at the time that mine would be the only chapter focused on a specific event. While the other essays explore broader themes across multiple fairs, mine is grounded in my long-term work at the Indiana State Fair—and especially in the Pioneer Village.

I feel fortunate to have served as a contributing curator for the exhibition. Much of my role involved sharing nearly two decades of research into craft traditions at the Indiana State Fair. I’ll be returning to the Renwick Gallery this winter to participate in a panel discussion, where I’ll speak about my work in arts and aging, drawing on experiences with longtime fair participants, including those in the Indiana Arts Building and across the fairgrounds.

JBJ: The new exhibition, book and public program series at the Renwick Gallery is one of scores of projects that you have pursued related to craft and craftspeople in Indiana, in the United States, and overseas. Looking ahead, what is your next big project related to craft all about?

JK: As you know, I tend to keep several projects going at once, so questions like this always make my head spin a bit. I recently submitted a manuscript for a book on Indiana basketry, which is currently under review at the press. It examines the social function of craft in everyday life and the cultural changes that have undermined it.

In addition, I co-authored a new, public-facing book, Lifelong Arts: A Creative Aging Handbook, for the Indiana Arts Commission. The Indiana Arts Commission will publish it. I wrote it with Stephanie Haines and Anna Ross, and it explores creative aging practices. The book is based on a series of public workshops and trainings that we conducted across the state in 2022-23. Lifelong Arts will be my third public-facing creative aging guide. This one is a more general guide to arts and aging. In contrast, my other two projects were regional and based on traditional arts and everyday creative practices: Memory, Art & Aging (Kay 2020) and Everyday Arts in Later Life (Kay, Jackson, and Islam 2024).

So, I am in the starting phase of two larger projects. One explores bowl hewing in Indiana, which connects to Keith Ruble, Bill Day, and the State Fair. While this tradition is deeply rooted in Indiana, I’ve also discovered that bowl hewing is part of a broader international network of green woodworkers, toolmakers, and heritage events. Many of these makers speak about how the craft supports their emotional, physical, and social well-being, which aligns with my ongoing interest in craft and wellness. The second project, which may eventually merge with the bowl hewing project, is a scholarly study on “Folklife and Creative Aging” (Figure 22).

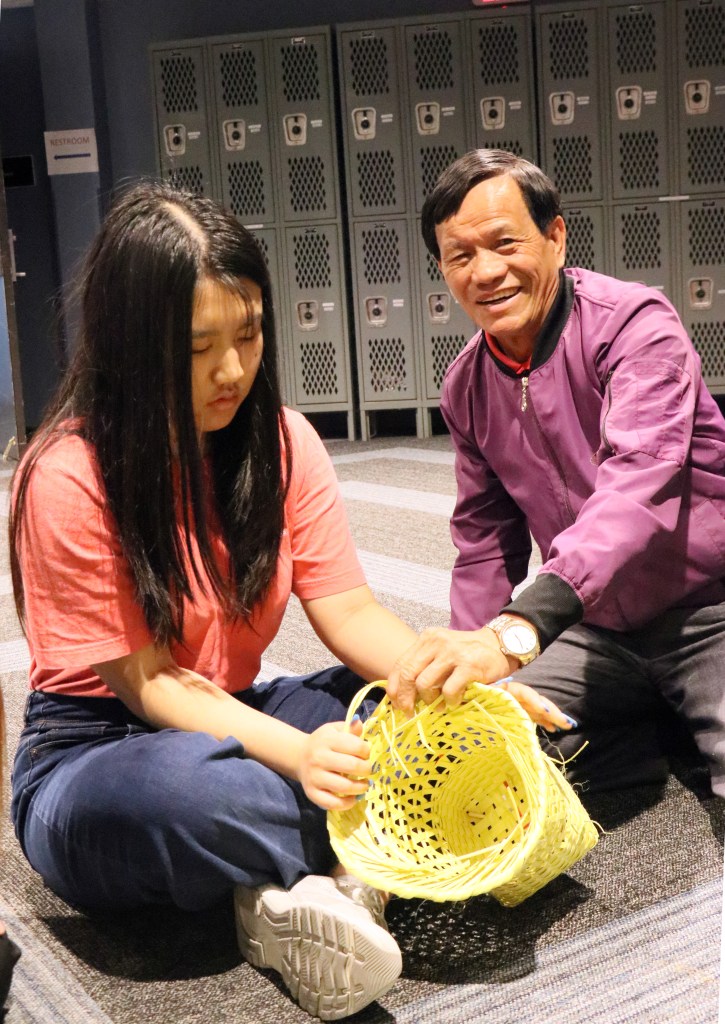

Of course, my academic research runs in parallel with (and within) my work directing Traditional Arts Indiana at Indiana University. TAI continues to operate the TAI Apprenticeship and the Indiana Heritage Fellowships. I am also exploring the development of an online version of TAI’s Community Scholar Training. It’s a lot to think about and seeing it all laid out like this feels a bit daunting.

In closing, Jason, thanks for your ongoing interest in craft, museums, and folklore. It was great to reflect on this moment and to think about my years at the fair and the exhibition at the Renwick. I know that the exhibition has helped me approach the fair with fresh eyes and to see the many crafts and communities that the fair has helped cultivate.

JBJ: Thanks Jon for sharing these valuable reflections and thanks for all that you do for Indiana and its peoples.

Learn more about the exhibition State Fairs: Growing American Craft online at: https://americanart.si.edu/exhibitions/state-fairs

A version of this post will be preserved in the Published Work and White Papers collection of the Material Culture and Heritage Studies Laboratory community in IUScholarWorks. [Update: See https://hdl.handle.net/2022/33755 for the archival version.]

Notes

*Twenty documentary videos profiling State Fair Masters are accessible via Indiana University’s Media Collections Online. See the “Traditional Arts Indiana’s State Fair Master Documentaries” collection via https://media.dlib.indiana.edu/.

References Cited

Kay, Jon, ed. 2020. Memory, Art, and Aging: A Resource and Activity Guide. Traditional Arts Indiana. https://hdl.handle.net/2022/33323

Kay, Jon, Joelle Jackson, and Touhidul Islam. 2024. Everyday Arts in Later Life. Traditional Arts Indiana. https://hdl.handle.net/2022/33322

Savig, Marty, ed. 2025. State Fairs: Growing American Craft. Smithsonian Books.