Who Cares About Craft as Traditional Knowledge?

This fall has been a particularly busy season for research-based programs at the Mathers Museum of World Cultures. An an outgrowth of our Indiana Folk Arts: 200 Years of Tradition and Innovation exhibition and our participation in classes and programs for Themester, we will have hosted, by semester’s end, a very large number craftspeople or groups of craftspeople representative of a broad swath of vernacular making in Indiana. Because of our Themester mandate to focus on questions of Beauty in our engagements with these artist-craftspeople, our discussions with them have always had an aesthetic component. We have asked, for instance, questions like: “What characteristics do you associate with a beautiful weaving [or chair, or drum, or pottery bowl, or…]?” or “When producing for the marketplace, how do you balance functional use and aesthetic impact?” Art and aesthetics are a crucial part of the human experience and of what makes cultures distinctive and meaningful.

But the objects that we curate and interpret, and the makers of things with whom we engage, are not only about art. Even while many have both aesthetic and functional purposes, many others of our museum’s objects are not reasonably framed as art and some of our interlocutors are talented, knowledgeable makers and users of things, without being artists. Our work is bigger than art, as important as art is. Aesthetic values are part of larger cultural systems and those larger wholes are our focus. Whether in China or in Indiana, our work is about local knowledge, including traditional cultural knowledge. A big part of our engagements with makers focuses on the knowledge that goes into making–craft expertise along with local environmental and contextual knowledge concerned with uses, meanings, significances.

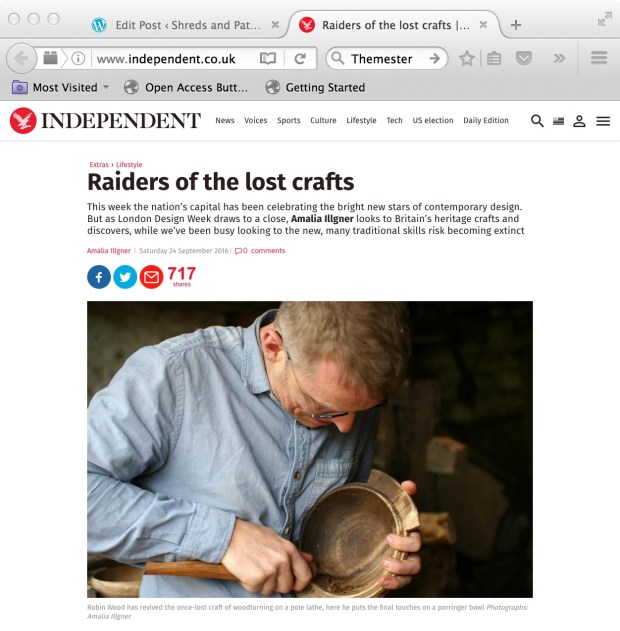

A detailed story in last Saturday’s Independent by Amalia Illgner is a good evocation of the kinds of concern we (particularly Traditional Arts Indiana, led ably by my colleague Jon Kay) try to bring to our work with craft objects, craft knowledge, and craftspeople. (I appreciate Matthew Bradley for sharing it with me.) Read the story (“Raiders of the Lost Crafts”) here. (I note here that, despite the declensionist hook and playful title, the author is not so obsessed with authenticity discourses that she disregards fruitful rediscovery of older craft knowledge through the study of museum collections and documentary materials. The story is a rare and rather sophisticated treatment of its subject.)

Who cares about craft as traditional knowledge? My colleagues and I do. We also like art and we also love seeing where contemporary craftspeople, including studio craft, DIY craft, and many others, are taking their passions–but documenting what people know and have long known is important and helping foster environments where those who have traditional cultural knowledge are supported and encouraged is key part of our mission. If you care about such things, you still have lots of chances to engage your interests at the museum this year. This week we will host a wonderful group of African American quilters and a talented maker of African drums. In following weeks, we offer chances to connect with Indiana limestone carvers, a hoop-net maker, a rosemaler, a pysanky artist, a Native American potter, a Zapotec weaver, and an Orthodox iconographer. Learning from such craftspeople is something we intend to keep doing as along as we can.