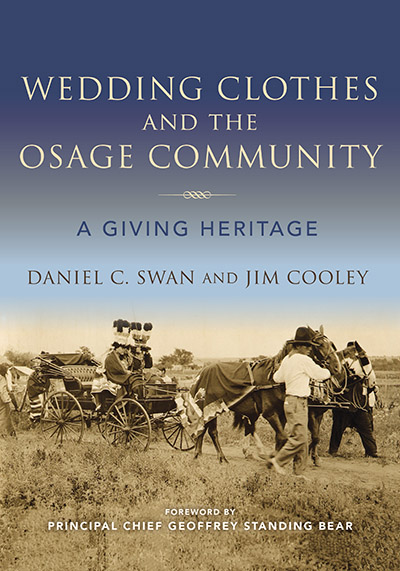

Below find the fourth of a series of guest posts offered in celebration on the occasion of our colleague and friend Daniel C. Swan’s retirement from the University of Oklahoma, where he has served with distinction as a Professor of Anthropology, Curator of Ethnology, and Interim Director of the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History. Reflecting here on an aspect of Dan’s work and his personal impact is Michael Paul Jordan, Associate Professor of Ethnology in the Department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Social Work at Texas Tech University. With me, he has co-organizied this series of guest posts. –Jason Baird Jackson

My Apprenticeship with Dan

by Michael Paul Jordan

I must admit that I approached the writing of this blog post with a great deal of trepidation. How does one distill a relationship into a piece of prose? You see, as an anthropologist, I have accrued debts, which I will never be able to fully repay. I owe a debt to the individuals, especially the many elders, who have shared their knowledge with me. I owe a debt to the communities that have welcomed me into their midst. And, I owe a tremendous debt to Daniel C. Swan. Understanding that whatever I wrote would fall short of capturing not only the profound influence Dan has had on my life, but also how much his mentorship and friendship mean to me, I decided to press on.

As a scholar who has devoted my career to studying expressive culture, I have an affinity for the master-apprentice model. I marvel at the Traditional Arts Indiana Apprenticeship Program, which pairs accomplished folk artists with eager students, facilitating the transmission of knowledge and skills to the next generation. If you look at the biographies of the artists, including the many Native American artists, who have been recognized as Heritage Fellows by the National Endowment for the Arts, you will see that many have been honored not only for their mastery of the mediums and genres in which they work but also for their efforts in perpetuating these artistic traditions. I count myself incredibly fortunate to have learned my craft from Dan Swan. At its best, graduate education resembles the master-apprentice model and I believe this is especially true when it comes to learning how to conduct ethnographic fieldwork.

I want to describe my own apprenticeship as a doctoral student at the University of Oklahoma and the lessons Dan taught me. Dan served as the chair of my dissertation committee. However, that official title cannot fully convey the influence and impact that he has had on my life. Over the past thirteen years, Dan has served as an incredible mentor and has become a dear friend.

Looking back, we can sometimes pinpoint the precise moment when a new chapter in our lives unfolded. A conversation with Dan in his office at the Sam Noble Museum marks such a moment in my own life. It was 2007 and Dan had just arrived at the University of Oklahoma. He had offered me a position as graduate research assistant, working with the museum’s ethnology department. He had also agreed to oversee an independent study course focusing on material culture studies. We were meeting to discuss the position and to hammer out a reading list. Much to my surprise, Dan didn’t usher me out of his office after thirty minutes. Hours passed and we kept talking. Dan’s enthusiasm was contagious. Here was someone who shared my interests. It was long after 5pm when we finally wrapped up. I left excited about the projects that I would be assisting with at the museum and eager to dive into the literature that we had discussed. This was exactly how I had hoped graduate school would be. I could hardly contain myself.

When I arrived home, hours later than my wife had expected, she could immediately see the change in my demeanor. My conversation with Dan had left me energized. This would not be the last time that Dan and I got carried away talking and lost track of time. In fact, that has become something of a running joke between my wife and I. It also would not be the last time that I emerged from a conversation with Dan feeling more optimistic, more confident, and more enthused than beforehand. There would be many such conversations. They occurred over lunch at places like Jump’s in Fairfax, Oklahoma or in the car driving to events in southwest Oklahoma. Such conversations have shaped who I am.

Shortly after Dan had agreed to chair my dissertation committee, we embarked on a series of projects that would have a profound effect on my understanding of what it means to be an ethnographer. The Brooklyn Museum had asked Dan to write a chapter on tipis and the warrior tradition for the catalog that would accompany the exhibit Tipis: Heritage of the Great Plains. He was kind enough to offer me a chance to coauthor the essay. We decided that we wanted to discuss the Kiowa Black Leggings Society’s (KBLWS) tipi, which had been painted by Dixon Palmer, a Kiowa WWII veteran. The tipi was inspired by the nineteenth century Kiowa chief Dohasan’s distinctive Tipi with Battle Pictures, which featured depictions of Kiowa warriors’ martial accomplishments. When Dixon painted the society’s tipi in 1974, he included battle scenes inspired by Kiowa veterans’ service in WWII, including paratroopers, Sherman tanks, and bombers.

During our interview with Dixon Palmer and his nephew Lyndreth Palmer, Commander of the KBLWS, we learned that the society had commissioned the painting of a new tipi to mark the 50th anniversary of the society’s revival. Subsequently, we received permission to film and document the painting of the new tipi.

At that time, the Sam Noble Museum was developing the exhibit One Hundred Summers: A Kiowa Calendar Record, which focused on a recently restored set of drawings created by the Kiowa artist Silver Horn to record 100 years of Kiowa history. Dan envisioned incorporating a series of short videos into the exhibit to highlight contemporary tribal members efforts to preserve their history. Footage of the painting of the new KBLWS tipi, which would depict Kiowa veterans’ service from the nineteenth century to the present, would enable us to discuss the ongoing relationship between art and historical memory in the Kiowa community.

Over the course of the project, we made multiple visits to Anadarko to document the progress of the painting. Dan and I interviewed the artists, Sherman Chaddlesone and Jeff Yellowhair, as well as Commander Lyndreth Palmer. On one of our visits, Commander Palmer asked Dan if the museum would be willing to film the society’s upcoming ceremonial. The Society does not allow filming of its ceremonies, so this request reflected the trust that had been established as we worked on the tipi documentary. Commander Palmer made it clear that the KBLWS would retain control of the footage and hold the copyright of the finished film.

Dan agreed and, in the process, he taught me an important lesson about relinquishing control and sharing ethnographic authority. At its core, Dan’s decision was about reciprocity and about honoring relationships. Commander Palmer and the KBLWS had supported our efforts, permitting us to document the painting of the Battle Tipi. Now, they were asking for Dan’s help. Would the museum support a community led initiative? Would it allocate resources for a project that was not tied directly to its own programming and exhibition goals? Dan, Mike McCarty, and I spent October 10 and 11, 2008 filming the society’s ceremonial. The museum would go on to produce a six-DVD box set for the KBLWS, featuring nine hours of footage.

Working on the exhibit, I also learned an important lesson about integrity and honoring one’s commitments to community members. As I noted, when we started working on the One Hundred Summers exhibit, we intended to create a series of videos highlighting community members’ grassroot efforts to preserve Kiowa history. Early on, Kiowa elder Florene Whitehorse-Taylor expressed her interest in documenting information regarding her ancestor, Chief Dohasan, who had led the tribe from 1833-1866. This seemed like the perfect fit, as Dohasan featured prominently in several events documented in the Silver Horn calendar.

As the opening of the exhibit grew closer, the curatorial team decided to focus exclusively on the painting of the Battle Tipi. While the museum’s plans had changed, Dan was adamant that we would make good on our commitment to Florene Whitehorse-Taylor and her family. Consequently, the museum produced Dohasan’s Legacy, a two DVD compilation of oral history interviews created exclusively for the descendants.

During these projects, Dan imparted lessons that continue to inform and guide my own work with Native American communities. These include lessons about the importance of relationships and of reciprocity. The project also taught me much about collaboration. In the years since the exhibit, Dan and I have spent time reflecting on the project and the lessons that we learned. We have even written about those lessons in the hopes that they might inform broader debates regarding museum-community collaborations.

Dan has done more than anyone else to shape my view of anthropology and my understanding of my role and ethical responsibilities as an ethnographer. By his example, he has challenged me to look for ways in which I can address the needs of the Indigenous communities in my own work. While Dan is retiring, I am confident that he is note done teaching. He still has lessons to impart and many of us, myself included, still have much to learn from him.

Dan and I standing outside the Forbidden City in Beijing, China. In 2019, Dan and I participated in the Seventh Forum on China-U.S. Folklore and Intangible Cultural Heritage, co-sponsored by the American Folklore Society and China Folklore Society. The conference theme was “Collaborative Work in Museum Folklore and Heritage Studies” and Dan’s presentation focused, in part, on the museum-community collaborations discussed in this post. Photograph by Dr. Kristin Otto