“A Culture Carried: Chin Basketry in Central Indiana”: Five Questions for Exhibition Curator Jon Kay

Jon Kay is Director of Traditional Arts Indiana, an Associate Professor of Folklore, and Interim Executive Director of Arts and Humanities, all at Indiana University Bloomington. In this exchange, I pose questions to him about his new exhibition A Culture Carried: Chin Basketry in Central Indiana. Find details about the exhibition and associated opening program at the end of the interview.

Jason Baird Jackson (JBJ): Thanks for taking time to field a few questions about the upcoming exhibition “A Culture Carried: Chin Basketry in Central Indiana.” For Shreds and Patches readers, I’ll share all the practical details about the show and the opening celebration below. Here, let’s jump right to an initial question about this exhibition and the work on which it is built.

Who are the basket makers whose work centers the upcoming exhibition at the Cook Center for Public Arts and Humanities in Bloomington?

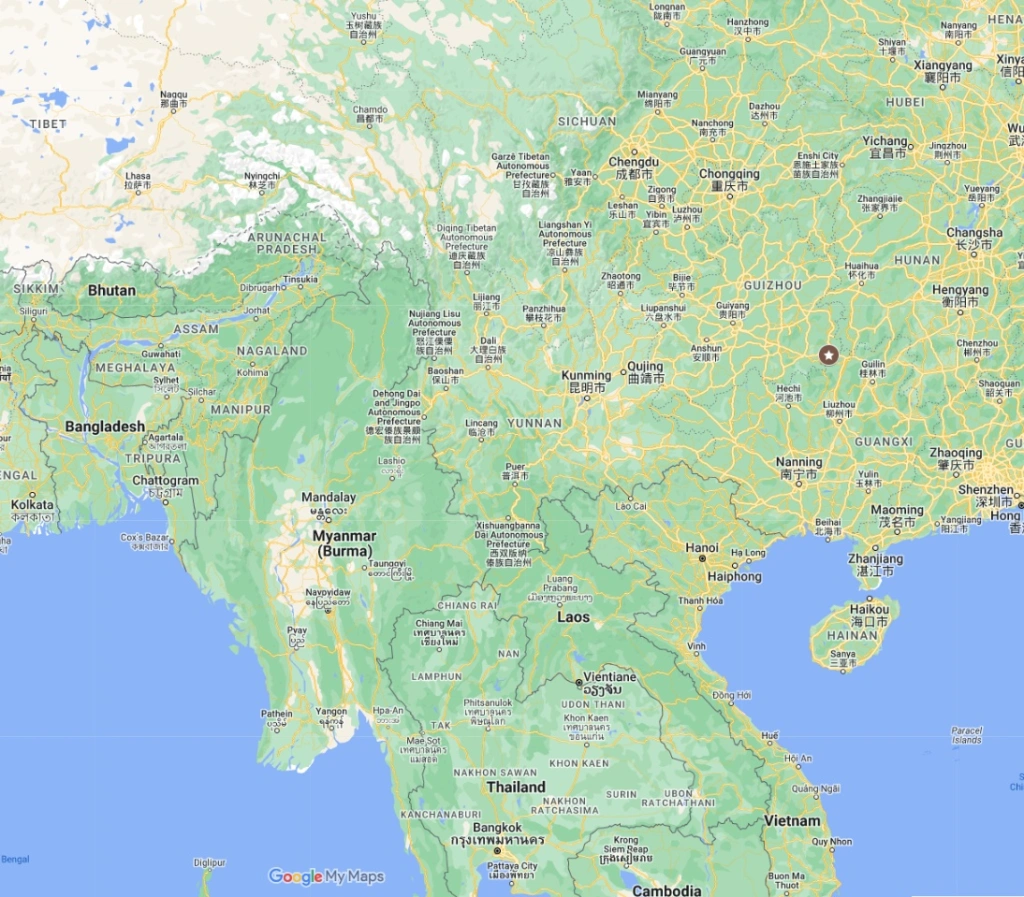

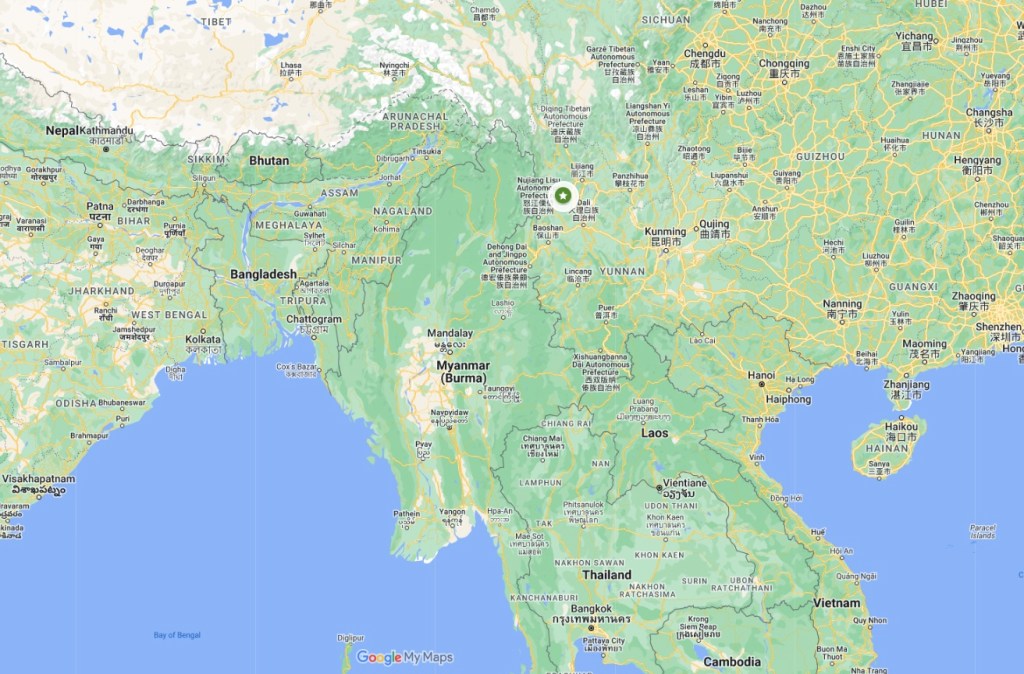

Jon Kay (JK): The exhibition features the work of Pu Ngai Chum and Reverend Ceu Hlei, lifelong friends from Chin State, Myanmar. Both are Zophei basket makers who now reside in Southport, Indiana, a suburb of Indianapolis with a large Chin refugee community. Pu Ngai Chum has lived in Indiana for over ten years, while Reverend Ceu Hlei came to visit his daughter in 2020 just before the pandemic began and ended up staying due to the ongoing turmoil in Myanmar. Following the military coup, civil unrest, and persistent violence against the Chin, he decided to remain in the United States with his family.

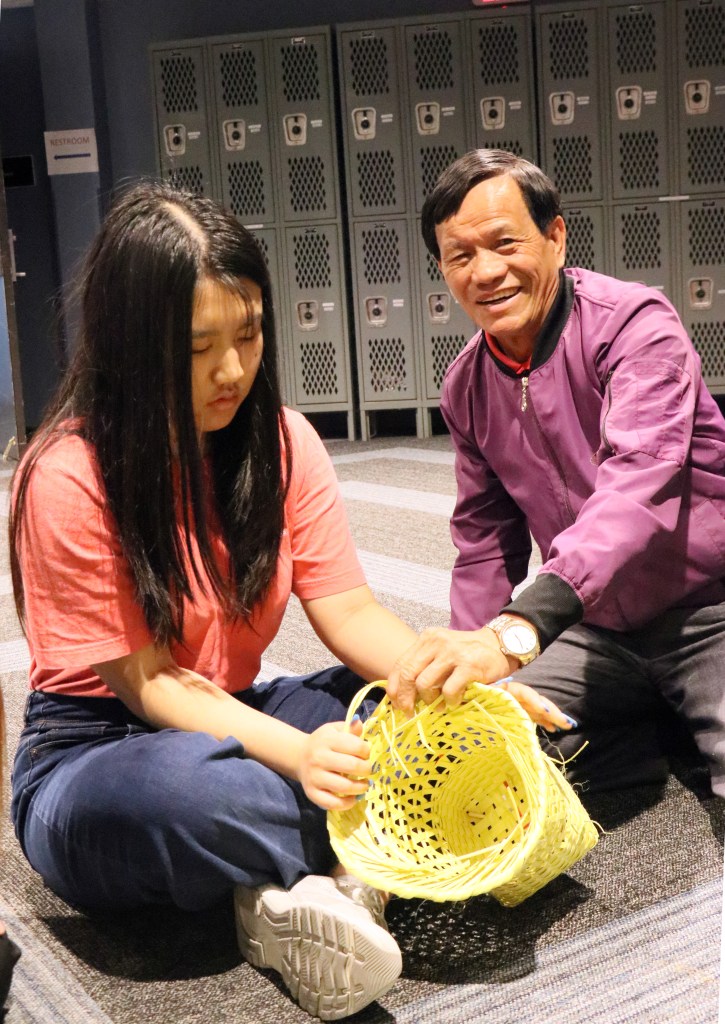

Pu Ngai Chum started making baskets for his Chin community after his children encouraged him to leave his job during the pandemic. Similarly, Reverend Ceu Hlei, feeling bored and depressed as a newcomer to Indiana and unable to leave the house, was encouraged by his son-in-law to start basket making. His son-in-law suggested he try using recycled polypropylene packing ribbon from local warehouses, just as Pu Ngai Chum was doing.

I met Pu Ngai Chum and Reverend Ceu Hlei about a year later while conducting a folklife survey on arts and aging in Central Indiana, funded by the Allen Whitehill Clowes Charitable Foundation. Since then, I have worked with them to coordinate basket classes, workshops, and demonstrations. All the while, I was buying baskets and documenting their craft, which led to this exhibition.

JBJ: I know that visitors will enjoy seeing their work presented in the new exhibition. Hopefully there will be a good turnout for the opening event where they will be demonstrating their skills publicly. That will be a great opportunity.

It seems to me that many people take baskets for granted. They are a kind of thing that one sees readily available in a store like Target. We rarely know where such baskets came from or who the people were who made them. When discussing your work with talented basket makers in Indiana, how do you find ways to shake people out of this passive relationship to this venerable craft?

JK: Other than the molded plastic laundry baskets and hampers sold by big box retailers—which arguably are not baskets— every basket is handmade. Today, their making may include special jigs, tools and machinery, but to some degree all baskets require some handwork and specialized knowledge. In the United States, some discount stores sell inexpensive baskets that are made in distant places where labor costs are low and manual skill is high. So, it is easy to speculate why baskets are met with apathy or even disdain.

When people want to invoke the idea that something is outmoded or simple, they may compare it to “underwater basket weaving” or call it “Basketmaking 101.” This position assumes that anyone can do it. While it is true that almost anyone could learn to weave basic baskets, few do. But if you look deeper into these woven vessels you begin to see they hold so much more. The sheer diversity of materials, patterns, aesthetics, and uses is staggering. From carrying eggs and catching fish, storing grain or serving food, holding babies to burying the dead, baskets for millennia have held our most precious possessions.

Moreover, the work that baskets and basketmaking does in the world is still needed. In many places baskets remain a part of everyday life. They are the perfect thing to carry to the market—no need for plastic bags. The feel of the twisted handle in my hand as I work in my garden each summer reminds me of how this old technology is perfectly designed for the work that baskets do in the world. But, more than the physical nature of baskets, basket making is needed now more than ever. In my arts and aging research, I see the value and power of creative pursuit in later life; something you can devote your time and attention to, a practice that gives you satisfaction and purposes, an activity that coaxes you into a state of flow. All of which support our wellbeing in later life…or for that matter throughout the life cycle. Too many young folks and elders in the United States, for example, are struggling with feelings of depression, boredom, and loneliness. Many find it difficult to forge meaningful relationships. Some are perpetual distracted with social media and portable technologies, and struggle with the basic human skill of human interaction with the world around us. Basket making is just one craft that requires mind and hand to work in concert. In addition, basket making can connect generations. Makers learn when they are young, often from grandparents or nearby elders then, when they grow old, they return to the craft to fill their lives with purpose in meaning. Moreover, when an elder teaches a younger person to focus and make a basket, they are also demonstrating them how to age well. In this light, I think we need more baskets, and for sure we need more people making baskets.

JBJ: Well said! And I think that your arguments about making and meaning also help us understand the remarkable transformations underway now at the intersection of craft and making activities and social media, particularly how-to videos for would-be craftspeople and makers, but also making-videos-as-entertainment, especially very short format videos of the kind visible on platforms like TikToc and Instagram. We can explore those themes another time but, building on them, could you say something about how you yourself use video and photography as part of your studies with basket makers such as Pu Ngai Chum and Reverend Ceu Hlei?

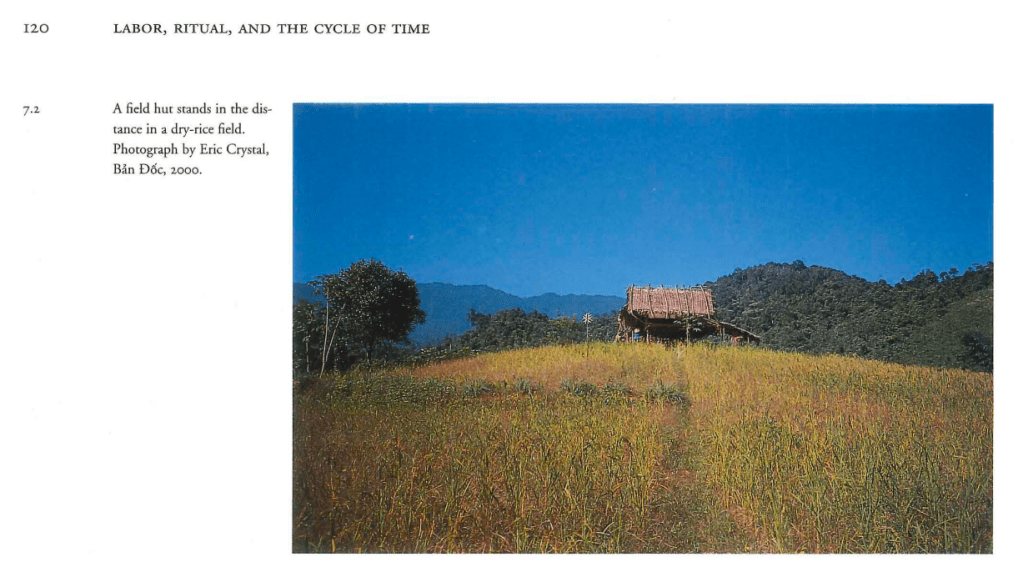

JK: Yes, you are exactly right. I have witnessed over and over how the documentary impulse is one of the ways that intergenerational bonds are strengthened. We could talk for hours about that, for sure. In the exhibition I include two documentaries that my research assistant Touhidul Islam and I made featuring the work of the two makers. They are great ways for exhibition goers to see how a basket comes together. Both videos compress a half day of work into a few minutes. And while I made them to share in the exhibition and online, that was just one of the reasons that I undertook those video making projects. First, the making of the video gave me a reason for engagement with the artists. I could tell them about my work, show them my publications, and visit with them, but when we collaborate in the making of the video, we learn about each other, and our trust grows. I have done five basket-making video projects all for the same reason. The first was with Viki Graber a Mennonite willow bask maker from Goshen, Indiana. The next was with Li Guicai a Baiku Yao basket maker who makes bamboo rice baskets in Southwest China. In addition to the two basket videos with the basket makers in the current exhibition, I recently produced a video that follows Myaamia artisan Dani Tippmann through the making of an elm bark basket. Each of these making projects (both the making of the basket and the making of the video) allowed the maker and the me to deepen our research relationship. It gave us a reason to work together. It was valuable to the maker, but also to me as video producer. Whether it is hosting a craft workshop, curating an exhibition, or making a video, my public-facing folklore work is more than just doing public programs, each activity creates a context for deep learning with my interlocutors.

I focus on process-centered documentaries. When I began this approach, it was less common for an ethnographic video to concentrate on a creative process. Instead, films would use footage of making as a backdrop for telling the maker’s story. However, in recent years process-centered videos have become popular. My social media feed is full of them. These videos are also very popular in the home communities where these tradition bearers are from.

I prefer making process-centered videos in part because the researcher and maker roles are even— the maker makes, and the documentarian shoots and edits. While we are working together; the maker knows what I am doing and what they need to do for it to be successful. As we work together, the maker tries to make the best basket possible, and I try to capture the best footage I can.*

JBJ: It is great to gain this sense of your process and your priorities in the work. That the videos will have multiple uses, both now and in the future, is a key factor. A classic gallery exhibition is a unique and wonderful thing—I have devoted my life to making them—but they cannot reach all audiences and they are very time and place limited. Your videos will do varied work around the world and in the Indiana Chin community itself. I look forward to watching them!

Can you say something about how this project and exhibition intersects specifically with Indiana University Bloomington, above and beyond its relevance to the Chin community, to Indiana as a state, and to TAI as the state public folklore program? Put another way, what connections already exist between IU Bloomington and the Chin people in Indianapolis and around the state? This is not the first time IU is engaging with Chin people, is it?

Yes, exhibitions have a limited reach, but they can signal to a community or group that we see them and that their work and culture is valuable both in their community and beyond. I have successfully used campus venues to prototype exhibitions, that I later expand and tour to venues nearer to the makers’ home communities. I did this with an exhibition about oak-rod basketry that was at Indiana University’s Mathers Museum of World Cultures but that was later installed at the Historic Brown County Art Gallery in Nashville, Indiana. Similarly, I did a small proof of concept exhibition on bowl hewing in Indiana at the Herman B Wells Library’s Scholar’s Commons that then was expanded to tour to the Swope Museum of Art. Just as video making is a process for fostering creative collaborations with the artists that I work with, so are exhibitions. Developing an exhibition, growing the exhibition, touring and programming the exhibition—all contribute to my greater understanding of the art form and the makers with whom I collaborate.

Back to your real question though… Back in 2010, Traditional Arts Indiana did its first project with the Chin community in Indiana. My graduate assistant at the time, Anna Mulé took the lead on that project, and we created a community exhibition and festival about Chin culture. Back then there were just a few thousand Chin living in Central Indiana. Today there are more than 30,000. I wish I could tell you that we continued to work with the Chin through the years, but we didn’t. In 2021, I received a grant to do work in Central Indiana focused on how everyday arts support elder wellbeing. It was then that I met my collaborator Kelly Berkson, an IU linguistics professor and the director of the Chin Languages Research Project (CLRP). It was in working with her that I learned about how much larger the Chin Population had grown. CLRP is doing amazing work documenting the diverse languages being spoken by the Chin peoples living in Indiana. Through Kelly and CLRP, I discovered that there were dozens of Chin students studying at Indiana University. Kelly had enlisted a strong team of Chin students to support her linguistic research and to understand what Chin languages are being spoken in Indiana. After meeting Kelly and her team, we decided TAI and CLRP needed to work together. Kelly and I received campus funds to support a summer collaborative project, the Chin Folklife Survey. The Chin students, Kelly, and Chin linguist Kenneth Van Bik, and I conducted interviews with elders in the Chin community. By recording their life stories, we developed a robust collection ethnographic interviews and linguistic data. The students loved the project. After that summer project, I began working one of Kelly’s students, Em Em, who graduated from IU with a degree in Public Health. She helped pilot a series of creative aging programs for Chin elders at the Chin Center of Indiana. From there, Em and community scholar Anna Biak helped start the Winding Wednesday group, a weekly gathering of Chin back-strap weavers living in Central Indiana. Pi Nah Sung has emerged as the lead teacher of that group. I say all of this to make clear that there is a network of students, community scholars, nonprofits, and university partners working with the greater Chin community in Indiana.

This exhibition would not exist if it was not for that constellation of collaborators. Kelly and her students introduced me to the community, students assisted me with translations and helped me understand the significance of basketry in their community. Em organized and facilitated basket workshops with the two makers, and her insights and knowledge supported this exhibition throughout its creation. This exhibition is not an expression of my “great curatorial understanding of Chin basketry,” rather it is a humble offering of respect and appreciation to the Chin community in general and to Pu Ngai Chum and Reverend Ceu Hlei specifically. It is my scholarly way of thanking them for their time and talent. I also hope the exhibit captures the interest of Chin students and that they might be inspired to learn more about the traditional arts of their community.

JBJ: It is super to get the wider Indiana University and Chin community contexts for the exhibition and for the larger project. That background really brings to life what is meant when we describe a research project as being a community collaboration.

You have been very patient with my questions at a busy time. You are not only finishing the exhibition and starting a new semester at Indiana University, but you are also working as Interim Executive Director for Arts and Humanities on the Bloomington campus. Take off your hat as Director of Traditional Arts Indiana and put on the A&H director’s hat. From the perspective of your new role, how does an exhibition like this one articulate with the larger body of work that faculty, staff and students at Indiana University Bloomington are now pursuing?

JK: The Arts and Humanities have long been one of Indiana University’s strengths. I feel very fortunate to be serving in this new role at this critical time. While I have been on the faculty at IU for twenty years, I have always identified as a public folklorist/humanist. My work has always aimed to serve the state, communities, and tradition bearers with whom I collaborate. Our university has undertaken of a seven-year initiative called the IU 2030 plan, which has three priorities. “Student Success & Opportunity,” “Transformational Research and Creativity,” and “Service to Our State and Beyond.” In some ways, this is just a rearticulation of the existing areas of review for university faculty: teaching, research, and service. The exhibition and the work that surrounds it delivers on the IU 2030 promise. I outline this below, not as a way of championing IU’s initiative or my work but rather to present how public humanities can work in a university context.

Student Success and Opportunity

Students were involved on all levels with the research, curation, and programs associated with the Chin basket exhibition. Chin students helped identify the basket makers and served as translators and fieldwork assistants. They worked with the Chin Folklife Survey, and gained insight into the fieldwork process, oral history skills, and how to translate field research into accessible content for their community. Folklore students worked alongside me in drafting the exhibition script, editing fieldwork video to be shown in the gallery, and selecting photographs to be included. These “real-world” experiences foster community pride and help develop important professional skills. In addition, they develop a portfolio of career-ready competencies to add to their resume before they leave the academy.

Transformational Research and Creativity

The exhibition also is an example of transformative arts and humanities research. While much of IU’s emphasis is in the biomedical and technology sector, one of the priorities of the 2030 plan is to “Improve the health and well-being of older adults through expansion of IU’s nationally recognized programs in aging research.” Since 2013, Traditional Arts Indiana has worked to research and present the ways that older adults employ traditional arts to resist feelings of isolation, boredom, and helplessness that beset so many older adults.**

The exhibition tells the story of older Chin who make baskets to give their lives purpose and meaning. Through baskets, and by extension all traditional arts, the exhibition shows how community-based arts work to connect elders to their community, fill them with a sense of satisfaction and mastery, and offers them a positive and culturally validating way to devote their time and attention. Over and over, my ethnographic projects focused on the expressive lives of elders reveal how traditional arts support elder wellbeing. Since “creative aging” is culturally situated and individually experienced, however, there needs to more research with and for the diverse communities we serve.

Service to Our State and Beyond

With recent changes at the National Endowment for the Arts, each U.S. state and territory is required to have a plan for supporting the folk and traditional arts practiced in their jurisdiction. In Indiana, Traditional Arts Indiana has done this work since 1998. This is one way that we serve the state. We host apprenticeships, award Heritage Fellowships, and produce exhibitions, recordings, and scholarship-based, public-facing works. The new exhibition is one of the ways Traditional Arts Indiana is serving our state. In addition to the service that our work provides to the state and for the Indiana Arts Commission, the state arts agency, the work that we do related to traditional arts and creative aging has helped shape arts and aging policies and programs across the United States. Moreover, our primary effort is always to serve the people of Indiana, including the Chin community in Central Indiana.

I should say that these are the way that I am framing my work given the current priorities of our University, but as a public humanist, I really have not done anything different than what I have done in the dozens of exhibitions, videos, publications, and projects that I have undertaken in since joining the faculty—I research, I teach, I serve.

JBJ: Jon, thank you so much for your time and for all that you do to support so many different communities and constituencies! As promised, I will now share the exhibition details. I look forward to seeing you at the opening events!

* Readers can learn more about Jon Kay’s approach to ethnographic video production with makers in his contribution to Asian Ethnology. See:

- Kay, Jon. 2022. “Craft and Fieldwork: Making Baskets, Mallets, and Videos in Upland Southwest China.” Asian Ethnology 81 (1–2): 273–78.

** In addition to major lectures in venues such as the Library of Congress, sources related to Jon Kay’s work on creative aging include the following two books:

- Kay, Jon. 2016. Folk Art and Aging: Life-Story Objects and Their Makers. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Kay, Jon, ed. 2018. The Expressive Lives of Elders: Folklore, Art, and Aging. Material Vernaculars. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

A Culture Carried: Chin Basketry in Central Indiana

OPENING SEPTEMBER 5, 2024

Chin Basket Weaving Demonstration by Pu Ngai Chum and Reverend Ceu Hlei at the “First Thursdays” Festival on the IU Bloomington Campus

Thursday, September 5th from 4 to 7pm on the Arts Plaza, Indiana University Bloomington

Bloomington Gallery Walk Exhibition Opening

Friday, September 6th from 5-8pm at the Cook Center for Public Arts & Humanities in Maxwell Hall (750 E. Kirkwood Ave, Bloomington, Indiana)