And Another Thing: University Presses

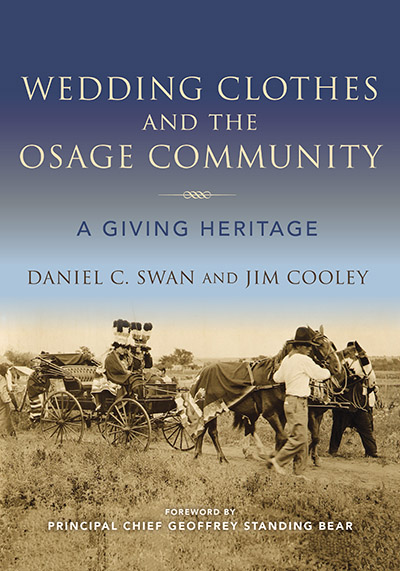

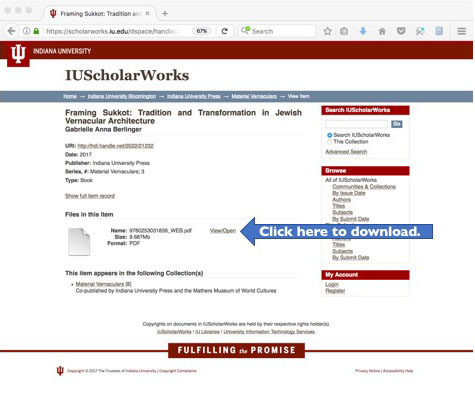

All, or almost all of the ACLS Scholarly Societies are in mutual aid relationships with university-based scholarly publishers (=university presses). In the case of folklore studies and the American Folklore Society (AFS), the most obviously relevant of these presses are (1) University of Illinois Press (which publishes the Journal of American Folklore (JAF) on behalf of AFS), (2) Indiana University Press (based at Indiana University Bloomington, where AFS is also based), (3) University Presses of Mississippi, (4) Wayne State University Press, (5) University of Wisconsin Press, and (6) Utah State University Press (now an imprint of the University Press of Colorado). Numerous other university presses in the United States are important to folklorists for various (often, but not only, area studies) reasons, but these six are particularly impactful through their (strong, specifically) folklore studies lists. They are also, like their peer presses strong in other fields, always working to innovate and take advantage of new affordances arising in our own time. Like our societies, they are not perfect but they are invaluable.

I have had a lot to say previously about university presses and scholarly communications more generally. Beyond talk, I have tried to do what I can. where I can to help. Here I just want to record again that university presses are themselves a crucial part of the ecosystems within which scholarly societies work generally, and in which folklorists and the AFS works, specifically. There are many threads woven together here and I will not unravel them at this point. Key at present is that those six presses of special concern to AFS members (call them the six most likely to send editors and books to the AFS meetings year after year) are all based at public universities. Things are more and more challenging at public universities like the ones that host these presses, especially anything seen from above to be part and parcel of the humanities, the social sciences, or the liberal arts tradition generally. The contexts in which the presses and some of us as individuals work are getting more difficult and administrators in varied locations are less and less willing to listen and learn learn about the important ways that university presses serve the universities that host them as part of a larger ecology of actors advancing research, teaching and service in the public interest.

So, when we do environmental scans of the state of our field, or when we pursue such things as a so-called SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats), we must keep the state of “our” university presses in mind. They have done, and are doing, important work with and for folklorists every day. In doing that work, they are also helping students and the various local audiences, publics, communities, and and collaborators with whom we engage. Given that all of the nodes in our network are experiencing new stresses, it is important that none of us in that network take any other node for granted. We must keep a lot of different things in view, including university press publishing.

PS: While I will not unpack the varied specifics here, the fate of university presses is linked to themes raised earlier in this series, including the discussion of AI, the reflection on Whac-A-Mole and, especially, the post on blocking scholarly societies from receiving public funds. Many other themes have not yet been raised in this series but could be.